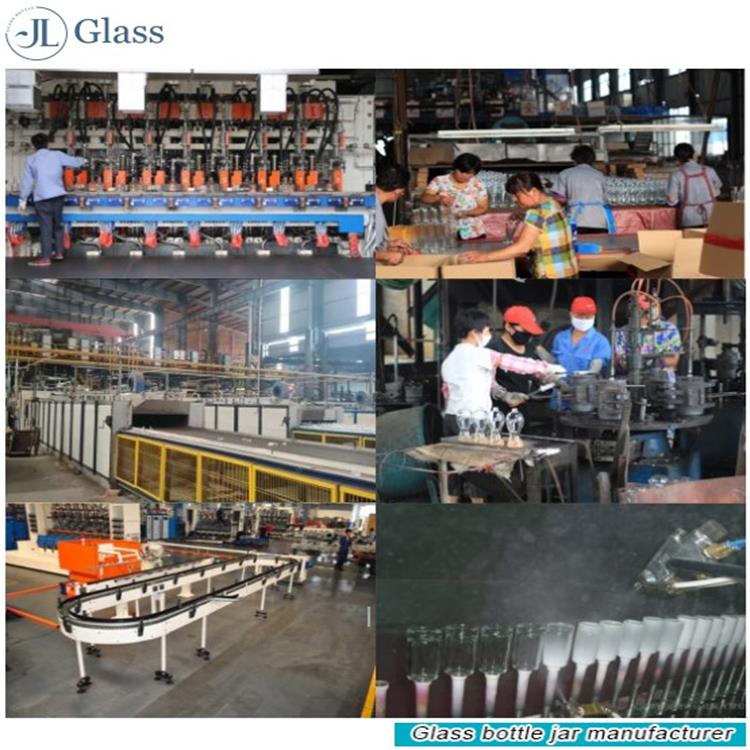

glass bottle production Background and Development

For centuries, glass goods were made by artisans using hand-blowing methods. Many products created by these highly trained craftsmen are found in art museum collections. Mechanization came to the glass-making industry with the Industrial Revolution and the subsequent introduction of pressing machines. This and other refinements promoted a range of new designs and uses of glass containers. Wide-mouth Mason jars became popular in the United States in the early 1900s, while the popularity of narrow-neck jars developed more slowly.

M. J. Owens and E. D. Libbey implemented a new process of glass bottle making by filling and dipping the first, or blank, mold into hot glass and evacuating the air from the mold. Several years of experimentation led to the development of an automated bottle machine. By 1920, 200 of these automatic machines accounted for approximately 45 percent of the total U.S.A Glass bottle making production.

In 1975, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued standards and guidelines covering waste water discharges from glass container manufacturing plants. The regulations targeted oil and grease pollution that originated from soluble oils used in glass shearing, machine lubrication, and condensation from compressed air systems. Oil and grease pollution stems from the biodegradable nature of the emulsified oil that subjects cullet-quench systems (broken or refuse glass added to new material to facilitate the glass-making procedure) to severe biological growth problems. According toGlass Magazine, biological growth within cullet-quench systems degrades oil and grease removal efficiency, often resulting in discharge values exceeding regulatory standards. In addition, the biologically fouled cullet-quench system precipitates a potential health hazard in the form of Legionnaire’s Disease and contributes to unpleasant working conditions.

A Packaging magazine survey in 1986 found that the promotion of glass containers had been successful. For several years, advertisers in the glass manufacturing industry had focused on the positive aspects of glass container use. At one point, glass container manufacturers sponsored advertising campaigns touting their product as a naturally pure, recyclable taste protector. The Nickel Solution Trust, which was formed in 1983 by a coalition of labor organizations and glass container manufacturers, was particularly innovative for the industry. Employees of glass container companies pledged a nickel of each hourly pay, and employers contributed matching funds, to pay for glass promotions. Since its inception, the trust has expended more than $21 million for recycling program development and management.

In 1997, production of glass containers totaled 247.4 million gross, which was outpaced by shipments of 254.5 million gross. The next year, glass container output was 256.4 million gross, but shipments were only 253.7 million gross. The production and shipment of narrow-neck containers consistently outrank those of wide-mouth containers. Shipments of narrow-neck containers in 1997 were 200.5 million gross, while shipments of wide-mouth containers were 54 million gross. In 1998, shipments of narrow-neck glass containers had risen to 200.9 million gross, and shipments of wide-mouth glass containers had dropped to 52.8 million gross. Wide-mouth containers are most popular for food, including dairy products, and sales and production remained steady. The lowest shipment and production levels were for narrow-neck and wide-mouth chemical, household, and industrial containers. At best, the glass container industry can be described as flat, with bottle shipments projected to remain flat, according to analysts. Continued overcapacity and the threat of conversion to alternative packaging are expected to keep price increases in the 3 to 3.5 percent range.

Several factors have contributed to the stagnant condition of the glass container industry. Since the 1980s, the glass container market has suffered a steady loss of market share to alternate plastic and can packaging. Analysts blamed the beer industry as a major factor in the decline of the glass container industry. More than 85 percent of the decline was due to brewers switching to aluminum cans, and industry leaders considered the lingering residual of this change would continue to pose an imminently significant threat. Although the shipment and production of beer bottles remained high, at about 88 million, analysts feared a decline as higher price tags forced consumers to switch to lower-priced canned beer.

The Glass Packaging Institute (GPI) considered one drawback to recycling was the forced deposit laws that require food packaging consumers to pay a deposit and then return the containers to the store for a refund. Such legislation is deemed devastating to the market share of environmentally friendly glass containers, and industry leaders argue that deposit laws influence consumers to opt for plastic containers. The GPI believes the most effective way to reduce solid waste is not by forced deposit laws but through comprehensive curbside recycling. The practice of bottle refilling as an alternative to recycling may undergo a comeback.

At the beginning of the 1990s five major glass bottling companies switched from plastic to glass containers because of consumer preference, environmental climate, and packaging costs, according to the GPI. According to investment analysts, however, falling resin prices had the potential of signaling a return to plastic. In 1989 a price differential of 20 percent between plastic and glass caused plastic to lose its market share to glass, primarily in the 16-ounce container segment. When the differential was closer to 5 percent or less, plastic regained some of its share. Until the glass container industry develops a more cost-competitive, lighter weight, or break-resistant package, analysts foresee fewer gains derived from anticipated growth in the soft drink market.

Raw materials left over from the manufacturing process created another challenge for the glass container industry. According to an industry spokesperson, only 85 to 90 percent of the melted raw materials are converted to a marketable product. The remaining 10 to 15 percent of raw material becomes cullet or discarded waste, mostly broken glass. Industry leaders were seeking satisfactory uses for this cullet.

During the 1990s the glass container industry continued to lose market share to plastic, although at a slower pace from the previous decade. For example, plastic containers used for beverages jumped from 14.3 million units in 1990 to 46.6 million units in 2000, while glass containers used for beverages fell from 30.7 million units in 1990 to 28.9 million units in 2000. Of the 244.3 million gross shipped in 2001, 51 percent of all glass containers were used for beer, which was the industry’s largest market category. Food glass containers accounted for 23 percent of shipments; carbonated and noncarbonated beverages, 9 percent; and wine, 5 percent.

Playing on glass’s image as being more trendy and prestigious than plastic packaging, the glass container industry hoped to overcome its drawbacks, including heavy weight that also increased shipping costs and breakability. As a mature industry, it struggled to identify new markets, but has reported significant growth in the ready-to-drink alcoholic beverages category. The increase in demand prompted longtime industry leader Owens-Illinois to open a cutting-edge facility in Windsor, Colorado, in 2005, the first new glass manufacturing facility built in the United States in two decades.